On Phronesis and Price Stability

‘With phronesis – practical wisdom. That is how the Eurosystem operates,’ said Klaas Knot on 28 November, at the Euro50 Group’s 25th anniversary at the Banque de France. He illustrated this with three examples: the ECB's balance sheet policy, the change in the neutral interest rate (r*) and recent supply shocks.

Published: 28 November 2024

© iStock

Thank you, Edmond. And thank you for organising today’s debate at the Banque de France – this is such a grand setting.

Testimony to that is the splendid Galerie Dorée, where we will have dinner later this evening. But even just walking in, you feel its historic importance.

© DNB

On the right side above the entrance on Rue Croix des Petits Champs, you can see a relief of the virtue ‘phronesis’.

It’s a female figure holding a hand mirror while a snake curls around her arm. The mirror symbolises the ability to see oneself as one truly is – which is a source of knowledge. And the snake refers to wisdom.

In today’s English, the Greek word ‘phronesis’ would be translated as ‘prudence’. But that doesn’t fully do justice to its origin. Phronesis is not so much ‘cautiousness’, but more ‘being able to do the rational thing at a given time and place’ – or shorter: phronesis refers to ‘practical wisdom’.

As such, I believe it is quite fitting that this virtue welcomes anyone who enters this building. As a matter of fact, I think it wouldn’t be out of place on every central bank building in the euro area. Because that is how the Eurosystem operates throughout all the changes our economies undergo: with phronesis, with practical wisdom.

Today, I would like to illustrate this with three examples: the balance sheet expansion at the effective lower bound (ELB), the changes in r-star, and the recent supply shocks.

First – the balance sheet expansion.

I became Governor of the Dutch central bank almost fourteen years ago. At the time, the euro area economy was just recovering from the global financial crisis (GFC). As it later turned out, the GFC marked an important shift in the macroeconomic environment.

In particular, we had to deal with deflationary pressures. These followed from the GFC and the sovereign debt crisis. But structural trends, such as globalisation, digitalisation, and demographic changes, also played a role.

Like other central banks, the ECB had to respond to these events. To fight the crises and support monetary transmission, the ECB intervened in financial markets by providing liquidity and securing funding for banks.

© DNB

But in dealing with deflationary pressures, the ECB also ran into the challenges associated with the effective lower bound. Easing the stance while conventional policy space was limited required the implementation of new, unconventional tools, including large-scale quantitative easing.

In hindsight, these policies were effective in staving off deflationary risks. What really helped, of course, is that both the tools for stance and other tools for transmission generally worked in the same direction: they eased financing conditions. But that does not mean that our toolkit comes without side effects.

For instance, one implication of the new policies is that they blurred the separation principle. This principle has been one of our guiding principles since the introduction of the euro. It basically states there should be a strict distinction between the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ of monetary policy – between formulating a monetary policy stance and creating liquidity, for instance as the lender of last resort.

But the large-scale balance sheet expansion – particularly the quantitative easing programmes of the past decade – made the ‘how’ an integral part of the ‘what’. Liquidity creation could now be directly linked to the way monetary policy was implemented.

Moreover, tools like the targeted longer-term refinancing operations and the pandemic emergency purchase programme were naturally hybrid – they were explicitly designed both to ease the policy stance and to stabilise markets and support monetary transmission.

Looking ahead, stabilisation tools will remain important elements of our toolkit. We might need them again to contain market dysfunction and support monetary transmission.

If you would ask me whether, away from the ELB, a return to the separation principle is desirable, I would say: yes, but in a different form.

As you know, our transmission tools have become more comprehensive: from traditional lender of last resort to a range of operations, including market maker of last resort. And with our new operational framework announced earlier this year, we will continue to operate with ample liquidity conditions.

Having said this, going forward, I do see some scope for a separation principle 2.0 – one that is no longer defined in terms of liquidity creation, but in terms of the purpose of a tool: steering monetary conditions versus safeguarding a homogeneous transmission.

Distinguishing the monetary stance from safeguarding monetary transmission makes sense because these operations may have to be implemented in opposite directions – like when the ECB launched the transmission protection instrument (TPI) at the same time it stopped net purchases under the asset purchase programmes. And even if policies pull in the same direction, we may – at some point – have to end one policy and continue the other.

For our toolkit, such a new separation principle would mean less scope for hybrid instruments, outside of the ELB.

TPI, is a good example of separating stance and transmission. It has enabled us to tighten policy decisively without unwarranted increases in sovereign spreads.

And so, I believe the ECB was exemplary in showing phronesis – practical wisdom – in dealing with changing circumstances. When needed, new tools were developed to provide liquidity and to ease monetary conditions. But going forward, we may want to separate instruments that steer the stance from those that support transmission.

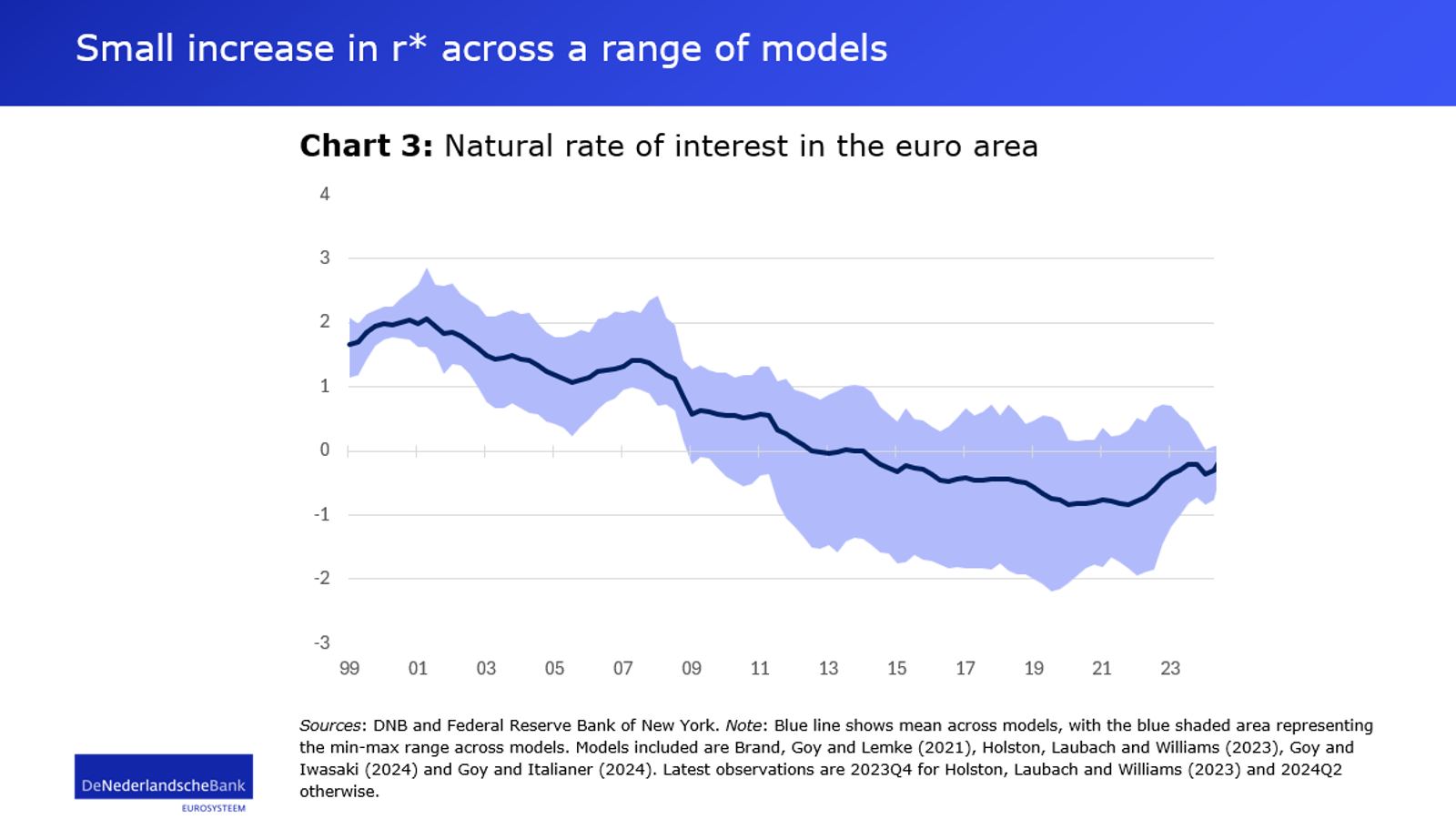

Let me now turn to my second example of phronesis: r-star, the neutral interest rate.

Of course, as an unobserved variable, r-star is subject to estimation and measurement uncertainty. On top of this, monetary policy recently had to deal with large and, above all, unprecedented shocks. These rendered our staff projections less precise. Additionally, the high pace of monetary tightening created uncertainties about the speed of transmission to the real economy.

Against this backdrop of heightened uncertainty, the ECB decided to follow a data-dependent approach. In particular, interest rate decisions would be based on the Governing Council’s assessment of, one, the inflation outlook in light of the incoming economic and financial data, two, the dynamics of underlying inflation, and three, the strength of monetary policy transmission.

The result was a remarkably fast and, to date, relatively painless process of disinflation. As such, monetary policy today is gradually winding down some of the restrictions, based on the same data-dependent approach.

But r-star is not only an important, albeit noisy, benchmark for monetary policy – it can also be informative for the monetary strategy.

© DNB

Over the last two decades, we have clearly seen a decline in r-star. A vast body of literature links this decline to lower productivity growth, higher risk aversion and safe asset scarcity, as well as demographic changes. (See, among others, Rachel and Smith (2015), Caballero et al. (2017), Mian et al. (2020), Gourinchas et al. (2022), Papetti (2021) or a recent speech by Isabel Schnabel (2024) for on overview.)

Since the pandemic, though, things appear to have changed, at least somewhat. Eurosystem estimates of r-star increased compared to pre-pandemic levels. The median estimate rose by about half a percentage point (Brand et al., 2024).

© DNB

According to DNB staff analysis – focusing for now on a single model – the increase in r-star since 2019 could be attributed to two factors.

First, a decrease in the convenience yield. This is consistent with the general increase in euro area government debt in recent years and an unwinding of the asset purchase portfolio. While the former may not persist if the new fiscal framework is successful, the latter is likely to persist for some time.

Second, an acceleration of the increase in the labour market participation rate. This creates a one-off boost to trend growth – as such, it increases r-star.

But again, let me reiterate that these numbers are derived from a single model and should therefore be interpreted with the usual grain of salt when we look at estimates of r-star.

Nevertheless, despite the recent up-tick in r-star, I think it is too early to speak of a trend reversal in r-star. And so, the phronetic thing to do for monetary policy is to be prepared to deal with future lower bound episodes.

So, to me, the most important part of the latest strategy review was acknowledging the ELB and how to deal with it. As such, the review concluded that – and I quote: “when the economy is close to the lower bound, this requires especially forceful or persistent monetary policy measures to avoid negative deviations from the inflation target becoming entrenched”. Unquote.

And still, the ink on the strategy review was still wet when the macro-economic situation changed again, and we experienced a series of rather persistent supply shocks. And as a result, inflation soared to historic heights.

Dear colleagues, after the separation principle and r-star, let me now turn to my third illustration of phronesis: the response to recent negative supply shocks.

Specifically, I think we must ask ourselves: how persistent should monetary policy be in a world with large supply shocks?

It is widely accepted that, in the face of cost-push shocks, fully stabilising prices leads to inefficient variation in output. That is why the ECB looks at the medium-term – and as such looks beyond temporary supply shocks.

The duration and magnitude of shocks are, however, unknown beforehand. Luckily, economic research may provide some guidance. As such, it may be optimal for monetary policy to look beyond temporary supply shocks as long as inflation expectations remain anchored (Beaudry et al., 2022), but to pivot aggressively once the risk of de-anchoring rises.

This research supports the policy reactions of the large central banks in recent years.

A related question we must also ask ourselves, is: how should we deal with persistent or near-permanent inflationary forces such as a declining labour force or deglobalisation?

To the extent that these structural forces affect potential output, counteracting their contractionary effects is largely ineffective. And, in terms of inflation, it may even backfire as high inflation may become entrenched. So, in the face of rather persistent supply-side shocks, monetary policy should focus on stabilising inflation.

Dear colleagues, I’m wrapping up.

I was invited here today to share some thoughts on what has changed in the conduct of monetary policy in the eurozone.

Indeed, quite a bit has changed.

And all those changes followed changes in the macroeconomic situation. Changes that required practical and rational responses.

I believe the ECB has shown a lot of phronesis in dealing with the economic shocks in recent years. And I may hope that this age-old virtue continues to guide us in the years to come.

For as long as we have the euro, the Euro50 group has been a valuable forum to discuss the monetary challenges that come with macroeconomic changes. This group is not called Euro25, so may this continue to be a place of inspiration and debate for at least another 25 years.

Thank you.

Discover related articles

DNB uses cookies

We use cookies to optimise the user-friendliness of our website.

Read more about the cookies we use and the data they collect in our cookie notice.